US-China trade war: European firms must diversify supply chains - PwC China Compass

17 June, 2021

The growing tensions between the US and China could have dramatic consequences for the reliability of supply chains and the innovation leadership aspirations of European firms. Excessive dependencies should be avoided and own standards promoted – even in markets outside the European Union.

Growing Chinese aspirations

Ever since Xi Jinping became president, China has been increasingly claiming a global leadership role. Domestically, firms are being encouraged to modernize through an enormous number of innovation policies. Internationally, this is complemented by the Belt and Road Initiative, which is promoting Chinese-led infrastructure projects in around 150 countries

China is setting standards on a global level

Setting standards is key

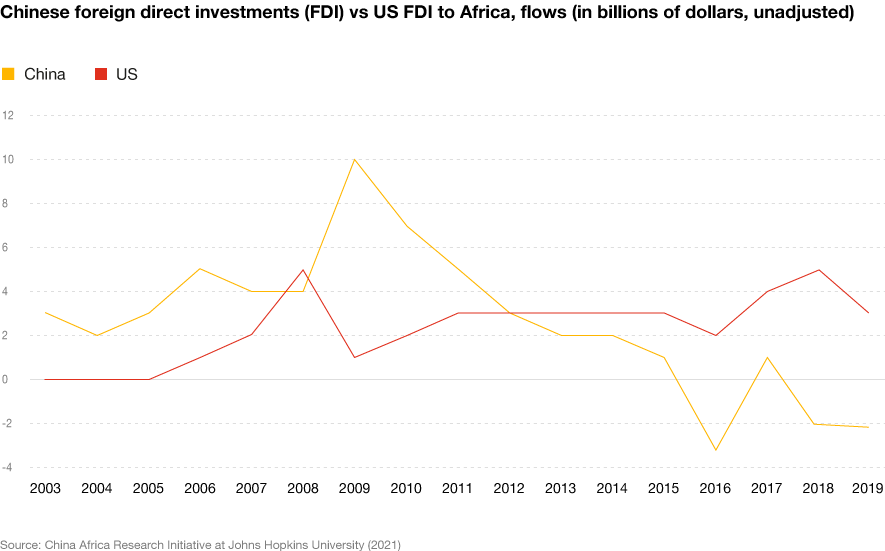

Simultaneously, these expansion programs enable the Chinese state to establish its technical standards on a global level. While for a long time European and American firms did not consider Africa an attractive market, Chinese firms are setting the framework conditions there for the digital world of tomorrow. A prime example is Nigeria, where, in a first step, Huawei provides low-cost 5G infrastructure, enabling further cooperation by other Chinese firms such as the state-owned satellite manufacturer China Great Wall Industry. The procurement of two satellites for Nigeria in 2018 was financed by China EXIM Bank, and the bank later paid $550 million for an equity stake in NIGCOMSAT, the Nigerian government’s satellite communications firm. The satellites help Nigeria identify potentially fertile soil at a lower cost than if it were to use images produced by the country’s own satellites or drones – an improvement made possible by financial support from Chinese state banks. At the same time, the Nigerian military is cooperating with the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) to investigate how Chinese drones can be used to fight the terrorist organization Boko Haram. While this allows the PLA to receive much lacking “combat experience,” Chinese intelligence services have an easy time tapping into new information – as the 2018 hack of the technical infrastructure at the African Union headquarters, installed by Huawei and ZTE, suggests.

It is precisely this intertwining of private and state interests, combined with a global expansionist policy, that is increasingly challenging the US’s hegemonic role. Like an ailing eagle, the number of wing-strokes the US needs to keep up with China seems to grow by the day: sanctions on the supply chain for chips, the ban on investments in Chinese tech firms, greater use of investment-screening mechanisms, and military initiatives such as the $27-billion US Pacific command.

For Europe, fostering R&D is essential

How European firms can respond

However, global deliveries for many European automotive OEMs mainly rest on the firms’ success in China. This is risky. How could European businesses move forward? First and foremost, by eliminating critical bottlenecks while diversifying supply chains. In addition, fostering R&D relevant to global supply chains is essential. SMEs can seek partners within European collaborative projects. Firms such as the Dutch semiconductor supplier ASML are a prime example in this regard. ASML’s expertise in manufacturing lithography machines, an essential component in chip making, is unmatched.

European firms should aim even higher, however, since the US has a virtual monopoly on the equipment used to make high-end computer chips, covering 80% of the market in some chip-manufacturing and design processes, such as etching, ion implantation, electrochemical deposition, wafer inspection and software design. Whereas much of the most advanced chip manufacturing takes place in Taiwan. Finally, not only can R&D spending lead to greater resilience, so can the development of own capacities in EU and global partnerships. Preliminary collaborations with India and Japan are pointing the way. By investing in the Global South, training people and building capacities, partnerships can be established on equal terms – notably in fast-growing markets such as Nigeria, Indonesia and Peru. For example, numerous Global South regions need assistance in building network infrastructure. Moreover, European firms could develop technologies to strengthen people instead of monitoring them. That would also allow Europe to offer an alternative to the hegemonic struggle playing out on the global stage.

Nils Hungerland

Email

Nils Hungerland holds an MSc in International Political Economy from the London School of Economics and studied International Relations (MA) in Berlin/Potsdam. He has worked in research, consulting and the public sector.

References

- Council on Foreign Relations (2021): “Assessing China’s Digital Silk Road Initiative”

- The Government of Nigeria (2020): “Draft for the Deployment of 5G infrastructure”

- Bloomberg (2021): “TSMC’s Global-Not-Global Strategy Must End”

- Nikkei (2021): “US-China tech war: Beijing’s secret chipmaking champions”

- Financial Times (2021): “West and allies relaunch push for own version of China’s Belt and Road”